Mogadishu – Somali journalists have a tough job. Their work is fundamental for sustainable development, human rights protection and democratic consolidation, but it can be a dangerous and sometimes deadly profession.

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s UNESCO Observatory of Killed Journalists, more than 1,600 journalists have been killed around the world since 1993 – dozens of those killings have taken place in Somalia.

This is in addition to other challenges. In her third visit to Somalia earlier this year, the Independent Expert on the Situation of Human Rights in Somalia, Isha Dyfan, spoke on the issue of media freedom in the Horn of Africa country.

“I remain dismayed by the continuing restrictions on civic space, including harassment, arbitrary arrest and detention and imprisonment of journalists and media workers leading to self- censorship,” Ms. Dyfan said.

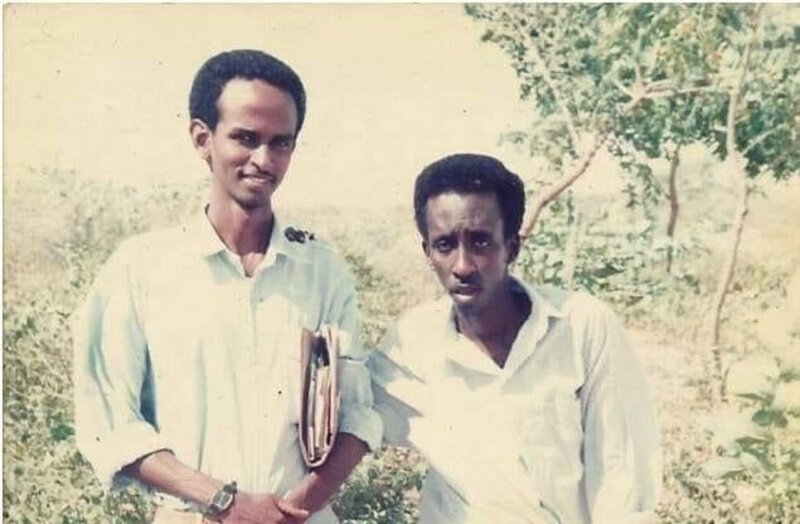

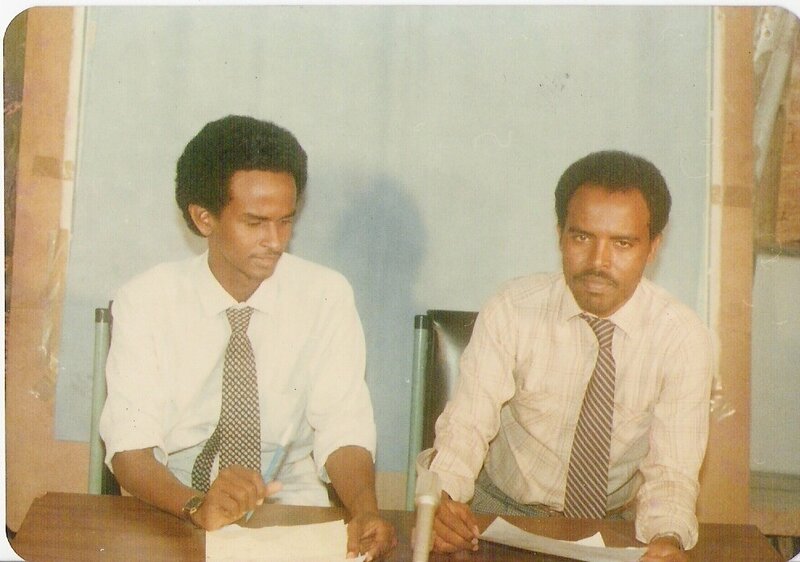

But amidst these challenges, there is one journalist who has carved out a niche for himself as one of the country’s most eminent media professionals: Farah Omar Nur, also known as ‘Maalim Farah.’

Over the past 40 years, Mr. Nur has become a well-known and respected figure within and outside of Somalia’s media sector as a combination of journalist, educator and advocate.

Wordy beginning

At a young age, there was no indication that Mr. Nur seemed destined to work with words. But his love of reading changed that.

He was born on 1 July 1960 in the Tiyeglow district, located 90 kilometres east of Hudur, the capital of the Bakool region in Somalia’s South West State. His birthday coincided with the day Somalia gained independence from Italian colonial rule.

He began his education in Tiyeglow, where he attended the district’s sole primary school from 1968 to 1971. In 1972, his family moved to Mogadishu, where the then 12-year-old continued his education at Howlwadag Primary School.

His schooling coincided with Somalia’s acclaimed mass literacy campaign in 1974–75. During that time, secondary schools were closed, and students and volunteers were sent to rural areas to teach people how to read.

When he was in the sixth grade, Mr. Nur was selected by the Ministry of Education to join the Rural Literacy Campaign. He was sent to teach in the village of Sabun, near the city of Jowhar in the Federal Member State of Hirshabelle.

“I taught close to a hundred people, including children and adults, to read and write in Somali over a period of seven months. It was the beginning of my journey to combat ignorance and advocate for the preservation and development of the Somali language, which carries a rich and valuable tradition and heritage,” he says, looking back at the formative experience.

In that nationwide campaign, more than 500,000 Somalis learned how to read and write.

Love story

After returning to Mogadishu, Mr. Nur continued his education at the Banadir Secondary School, graduating in 1979. He then enrolled in the Faculty of Journalism and Communication Science at the Somali National University (SNU) in 1982, joining the third cohort of students following the academic institution’s opening in 1980.

“At that time, I chose journalism out of love. I had followed news developments on the radio and newspapers closely and had thought about enrolling in a journalism course,” Mr. Nur says.

“While I was in high school, I often heard that the nation’s university would be establishing the faculty in the 1980s,” he adds. “I eagerly anticipated the establishment of the journalism college and enrolled with great satisfaction and immense joy, two years after its founding!”

Mr. Nur graduated in 1984 and, a year later, he joined Somali National Television (SNTV) as a reporter and producer.

“While working in government-owned media, I produced special programmes and reported on government activities according to its directives. At that time, there were no independent (private) television or radio stations. Those of us who admired the media had to channel our passion within the confines of government-controlled media,” he recalls.

War breaks out

Mr. Nur’s employment at SNTV ended in 1991 as the country descended into its decades-long civil war. In the early days of the fighting, armed groups broke into the locked-up premises of the national broadcaster’s premises and looted or destroyed most of its equipment.

Nonetheless, Mr. Nur decided to remain in Mogadishu and continue informing the Somali public.

“Many of us, myself included, were hopeful and believed that the nation would soon find its way back to peace. I wanted to contribute to the peace efforts being made by both Somalis and the international community,” the veteran journalist says.

“Although the situation has been troubling for some time,” he continues, “I remain committed to preserving and strengthening the peace we have established. It is crucial to understand that the peace we have today is fragile and requires our continuous commitment and effort to maintain and improve it.”

With SNTV closed and no central governmental authority in place, Mr. Nur founded a newspaper called ‘Isha’ (transl.: The Eye) to cover the country’s news.

Unfortunately, just a year later, armed bandits entered the newspaper’s premises and stole its printing equipment – dashing Mr. Nur’s hopes for an independent news media outlet to report on politics and social affairs.

Mr. Nur sought employment elsewhere. He worked for local newspapers such as Gorgor, Kulan, and Qalam – news outlets that eventually closed down due to the impact of the country’s conflict – until 2005, when he joined the BBC World Service Trust, which was re-named BBC Media Action in 2011. He covered social issues such as economics, culture, droughts and sports until 2014, but also delved into other kinds of programming.

“I wrote dramas like ‘Dareemo’ (transl.: Grass) and ‘Maalmo Dhaama Maanta’ (transl.: A Better Life Than Today). These dramas were entertaining but also aimed at helping change people’s behaviour and inspire our youth to dream of a better future,” he says.

Many roles

Mr. Nur’s links to the BBC continue to this day – he currently works as a consultant on drama script-writing for BBC Media Action.

This work is in addition to other current roles: journalism lecturer at his old alma mater, and Secretary-General of the Federation of Somali Journalists (FESOJ), the leading umbrella association for media professionals and news outlets in the country.

In a way, they are all inter-related.

“The university I graduated from in 1984 reconnected with me in 2019 when the head of the Faculty of Social Sciences approached me at FESOJ with a request to lecture at Somali National University’s journalism faculty. The college has always held a special place in my heart, so I accepted the offer,” Mr. Nur says.

“I have been working part-time at the university,” he continues, “and have had the privilege of lecturing on conflict reporting, media management, and principles of communication to the last three graduating classes.”

The SNU reopened its Department of Journalism and Communication in September 2017 with an inaugural class of 60 students. Three cohorts of journalism students have graduated since then.

Media advocacy

Mr. Nur had been a long-serving member of FESOJ, in its previous iteration under a different name, and in 2019 he became its training secretary. In 2020, he was elected as the association’s Secretary-General, charged with advocating for the interests of journalists and media houses in Somalia.

“I believe that Somali journalists can play a key role in peace and security if their skills are enhanced, and current challenges addressed. Responsible journalists armed with the truth are essential for the country’s progress,” Mr. Nur says.

“Under my leadership,” he continues, “FESOJ, in collaboration with international partners including the United Nations, has trained nearly 3,000 people in Somalia – that’s nearly 3,000 journalists and civil society members – over the past three years.”

Mr. Nur acknowledges the immense challenges faced by Somali journalists and states that FESOJ aims to create a better environment for them.

Amongst its goals, FESOJ strives to promote, safeguard and defend the professional interests, welfare and status of working journalists; promote and maintain the highest standards of professional conduct and integrity and to strive for and defend the freedom and independence of the media; and, monitor and investigate violations of press freedom and human rights of journalists.

According to the non-governmental organization the Committee to Protect Journalists, 79 Somali journalists were killed since 1992.

Given his wide-ranging experience in the media, many of the victims were not unknown to Mr. Nur.

“From the onset of Somalia’s civil war until now, I have witnessed severe abuses and killings of Somali journalists. This situation was particularly shocking for me because I knew many of these journalists personally – I had met them face-to-face and, in some cases, had even provided them with training and support. Each atrocity left a profound and distressing impact on me,” he says.

That added personal element infuses his approach to advocacy work.

“I constantly think about how to address the challenges faced by Somali journalists, if they are imprisoned, persecuted or killed, or just seeking training to fulfil their responsibilities in alignment with freedom of speech,” he adds. “Essentially, how we can create an environment where Somali journalists can work more safely and effectively, enabling them to pursue their work with integrity without infringing on anyone’s rights.”

He believes that journalists equipped with the right skills and ethics are crucial for the development of a responsible media in Somalia.

“While my colleagues and I work hard to enhance the skills of Somali journalists, we acknowledge that the road ahead is still very long. However, we remain optimistic about overcoming the current challenges related to the lack of training in journalism, especially as more young journalists continue to enter the field each day,” he says.

FESOJ currently has 560 members across Somalia.

According to the SNU’s Department of Journalism and Communication at the Somali National University (SNU), some 75 young Somalis have graduated from its courses as of 2023.

“Mr. Nur is the backbone of our students’ development, and they rely on him greatly. He serves as an exemplary role model. There are very few individuals in the country with his level of experience. He is a significant asset who has made substantial contributions to the journalism department at the nation’s university,” says the faculty’s Dean, Professor Abduqadir Dhidisow, adding, “It is crucial to have people like Mr. Nur contributing to their education.”

UN support

The United Nations advocates for the significant role that the press, journalism, access and dissemination of information play in ensuring a sustainable future.

According to the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), media freedom and access to information feed into the wider development objective of empowering people, and empowerment is a multi-dimensional social and political process that helps people gain control over their own lives. UNESCO goes on to state that this can only be achieved through access to accurate, fair and unbiased information, representing a plurality of opinions, and the means to actively communicate vertically and horizontally, thereby participating in the active life of the community.

In Somalia, the United Nations supports media development through its work with various media associations around the country. In the case of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM), that support includes for FESO.

“The media have an important role to play in Somali society as the country rebuilds and continues on its path to stability and prosperity, and having such an experienced and respected veteran like Maalim Farah to advocate ably for the profession at the head of FESOJ, but also teach new generations while still working as a journalist, is a huge bonus for journalism in Somalia,” says Ari Gaitanis, the Chief of the Strategic Communications and Public Affairs Group (SCPAG) at UNSOM.

“On a more personal note, in every part of Somalia I have been to, from north to south, it’s impressive how every Somali journalist I have met knows of Maalim Farah, and acknowledges and appreciates his role in and contribution to their country’s media development,” he adds. “It says a lot about him and what he brings to the table.”

UNSOM’s support to FESOJ has centred on training journalists around the country on areas ranging from hands-on skills such as news writing and video camera operations, to more thematic areas of reporting such as electoral processes, women’s political participation, freedom of expression, climate change, and issues affecting youth, women and marginalized groups.