Tuesday 18,March 2025 {HMC} At precisely midday, the sound of a bell rings out across the grounds of the Mustaqbal Integrated Primary School, located in the midst of camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Baidoa, in Somalia’s South West State.

It signals the start of lunchtime, and the school’s 2,000-plus students spill out from classrooms into the lunch and play areas. Among them, are more than 400 students with disabilities, ranging from 12 to 20 years of age.

Amidst the sea of yellow and white uniforms, teaching staff – including the school’s principal, Habiba Ibrahim Aden – fan out into the lunch space to distribute meals to pupils in early childhood development classes and to students with disabilities.

The work is constant but, as she passes out lunch trays to students, Ms. Aden has a look that combines a sharp-eyed alertness with pride and determination – the school has come a long way since she established it in 2017.

Beginnings

Ms. Aden was born in the town of Berdale, in the South West State’s Bay region, in 1981. She went to the Baidoa Model School for her primary and secondary education between 1998 and 2010, before undertaking an undergraduate degree in public administration at the Imaam University in Mogadishu, from which she graduated in 2020.

After her studies, she begun working at her family businesses, which involved restaurants and clothing shops at Baidoa’s main marketplace.

Then, things changed in late 2016.

“One morning, I was sending my children to school and noticed a young girl timidly following her siblings. Suddenly, her mother emerged, seized the girl, and forcibly brought her back inside their home. The mother’s anguished cry echoed: ‘What can you learn? You’re deaf,’” Ms. Aden recalls.

“From that moment,” she adds, “I resolved to safeguard the future of that girl and others like her in my community.”

One of her first steps was to find out what resources were available and required for children with disabilities in her area. Her findings were not encouraging: there was a glaring absence of inclusive learning facilities for children with disabilities in Baidoa.

So she started one.

“In March 2017, I established Mustaqbal Integrated Primary School with 13 students with disabilities. Less than a decade later, more than 2,000 students – primarily from vulnerable communities – are now receiving free primary and secondary education. I consider this a remarkable achievement,” Ms. Aden says, a note of pride in her voice.

Parental challenges

In Somalia, students with disabilities often struggle to conform to societal norms, leaving them vulnerable to social challenges such as discrimination, bullying and mistreatment from their peers. This has led many parents to keep their children away from educational institutions.

“The biggest challenge we face is parental reluctance to send their children with disabilities to school. They fear social stigma, intimidation, and humiliation from other students. They also doubt their children’s capacity to learn,” Ms. Aden says.

“It can take more than six months to convince some parents to enroll their children,” she adds. “They often set unrealistic expectations, demanding literacy skills within a mere three months or threatening to withdraw their children.”

While dealing with these issues with parents can be disheartening, Ms. Aden and her team persevere – often it is the students with disabilities who provide that boost of motivation for them.

“I dream of becoming an educator for children with a hearing impairment – once I complete my studies, I will dedicate myself solely to this career,” explains 44-year-old Fadumo Ali Ahmed, a first-year high school student with hearing loss, through a sign language interpreter.

External support

The Mustaqbal Integrated Primary School is made up of six buildings housing 35 classrooms. Its operations are vital for local communities of displaced people, but funding still remains a challenge.

“Currently, there are a total of 2,054 students, comprising 851 girls and 1,203 boys, primarily from neighbouring IDP camps. We also have 42 teachers, 21 paid by the Food and Cash Consortium and eight by Save the Children. The rest are unpaid due to a lack of resources,” Ms. Aden says.

In addition to the Food and Cash Consortium and Save the Children, the South West State Ministry of Education, the Somali Water and Sanitation Authority, international non-governmental organisations and the United Nations have assisted the school with financial and logistical support.

From the UN family, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has had a leading role, which has also included covering school-fees for some students in the past, among other forms of support.

“With the recommendation of the SWS Ministry of Education, UNHCR provided vital support. They fenced the entire school with a hard wall to reduce external threats and provided a school bus for disabled students – this significantly increased enrolments, as many parents are wary of public transport or cannot afford the fees,” Ms. Aden says.

“We have actually requested another school bus,” she adds, “as the current one is insufficient due to the increasing number of students with disabilities joining the Mustaqbal Integrated School.”

When considering the situation of these students across Somalia, Ms. Aden ventures that there is an urgent need for more teachers trained on assisting them.

“Recently, the Federal Government of Somalia’s (FGS) Ministry of Education hired 6,000 teachers. Shockingly, not a single one is qualified to teach Braille or sign language. This highlights the lack of inclusive learning opportunities in Somalia. We urge the FGS to consider the rights of students with disabilities when recruiting teachers,” she says.

UNHCR’s role

According to ‘A rapid assessment of the status of Children with Disabilities in Somalia,’ a 2020 report commissioned by the Federal Ministry of Family and Human Rights Development, persons with disabilities in Somalia struggle to be recognized, gain access to resources, and feel valued in their community.

The number of children with disabilities is estimated at between three and five per cent of the children’s population. In regard to learning, the right to education is hampered by acute lack of human, infrastructural and financial resources. Most children with disabilities attend normal schools, while a few attend special schools.

The report also found that awareness about the rights of children with disabilities is increasing, but is still low in some quarters and the attitudes within a large swathe of the community towards children with disabilities is still remains rather negative. Similarly, skills for supporting children with disabilities are still largely lacking.

From the UN family, the UN’s refugee agency has been actively providing lifesaving and protection assistance for displaced Somalis for more than 30 years.

“The Mustaqbal Integrated Primary School is a supportive learning centre for students with disabilities as well as students without disabilities from poor families. In its lead role on the protection of Somalis who have been displaced by conflict and climate change, we have been advocating for the support of the school to encourage persons with disabilities to have access to education,” says UNHCR Field Associate Abdikarim Mohamed Noor.

“Between 2017 to 2025,” he continues, “UNHCR’s and other partners’ support contributed to the growing number of students enrolled here – from 42 in the early days to more than 2,000 now – with students with disabilities making up a large percentage of these.”

In addition to the school bus and the construction of the school perimeter wall, UNHCR has previously supported 112 students with payment of their school fees for a year.

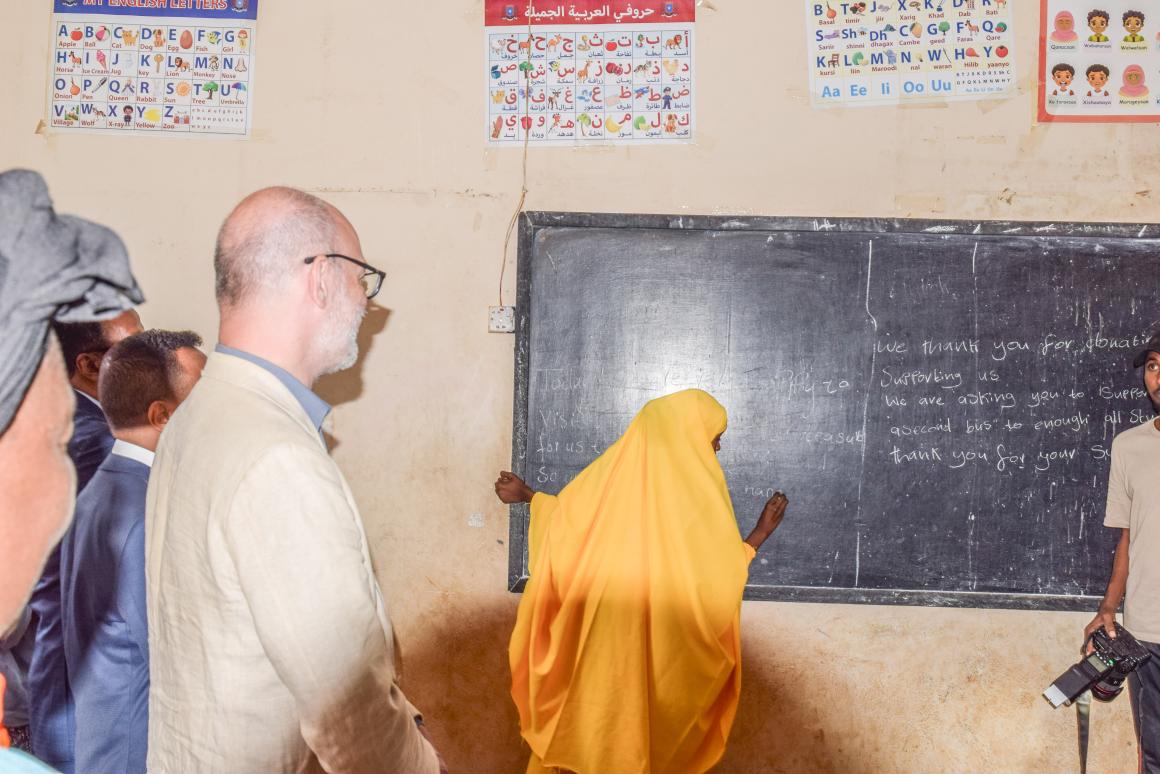

The UN Resident Coordinator for Somalia, George Conway, visited the Mustaqbal Integrated Primary School in 2024 for a first-hand look at its operations and impact on the local community.

“It’s the grassroots efforts of people like Ms. Aden that can really help make a difference for children with disabilities who would not be able to easily access educational facilities – this is step towards ensuring they’re not left behind,” says Mr. Conway, who also serves as the UN Secretary-General’s Deputy Special Representative for Somalia and Humanitarian Coordinator.

“I commend her on what she has achieved, and hope it can inspire others to step up, engage and support,” he adds.

The rights of Somalis with disabilities received a boost recently, with the Federal Parliament’s passing of a Disability Rights Protection Law. It guarantees rights to education, health care, and employment while holding institutions accountable for inclusivity. The law’s key focus is accessibility and inclusion, requiring schools and other institutions to provide inclusive education to meet the needs of students with disabilities and protect those disabled during emergencies.

The United Nations in Somalia has welcomed the law, describing it as significant legislation designed to protect the rights and dignity of persons with disabilities.